Threats from Habitat Loss

Habitat loss is a primary threat to the survival of monarch butterflies, depriving them of the food, water, and protected. In Marin, the native ecosystem has been dramatically changed by human activities, including commercial and housing development as well as agriculture.

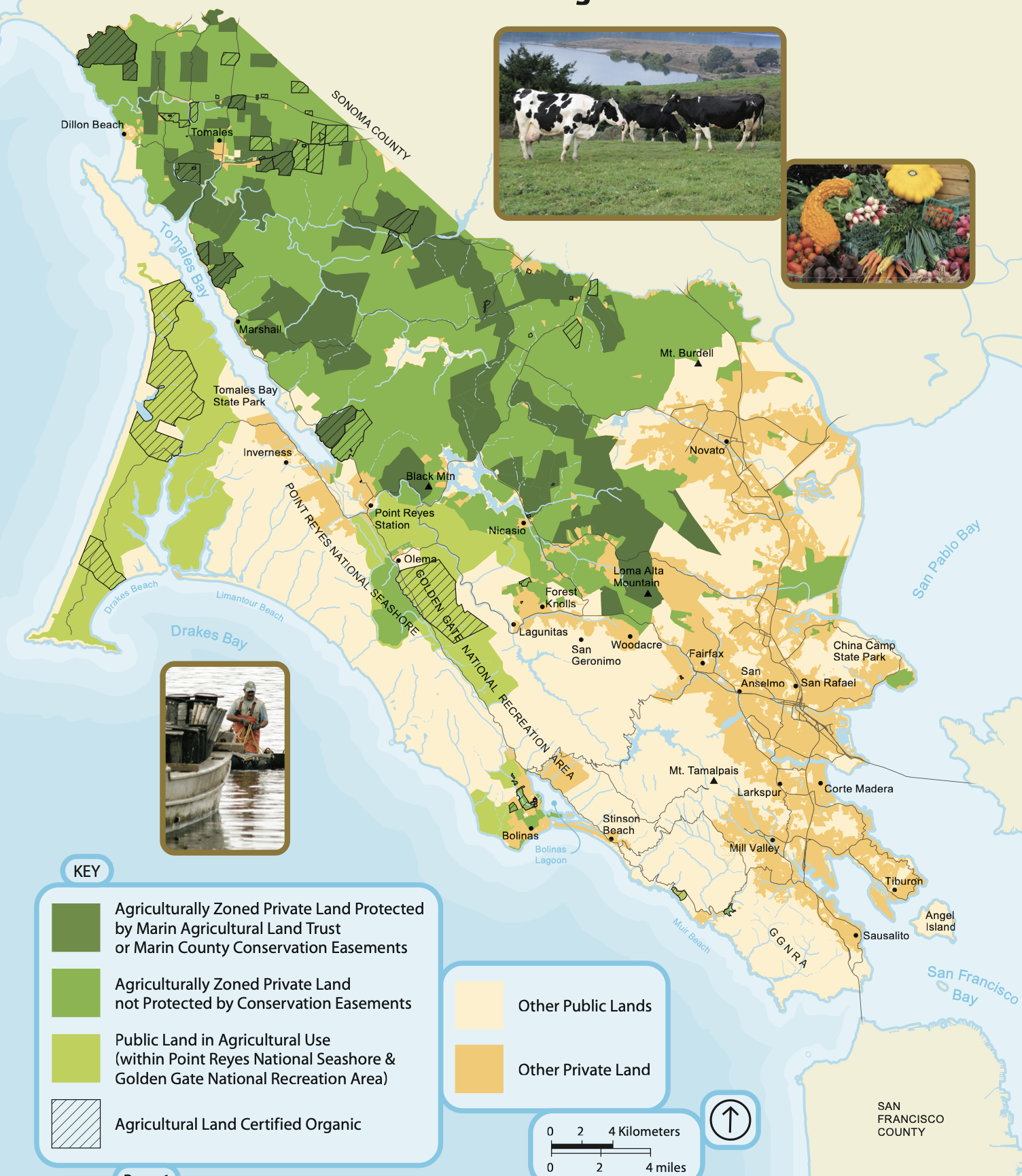

Roughly one third of the the 606 square miles of land and water in Marin consists of protected open space, watersheds, tidelands, and parks. Another half of Marin’s land is occupied by farms and ranches and the remainder is composed of developed areas, primarily within cities and towns. Habitat loss presents a particular problem in the agricultural and developed areas.

Habitat destruction occurs when native habitats are replaced by housing and commercial development. It also includes such acts as filling in wetlands and damming rivers.

Habitat degradation occurs when pollution degrades the quality of habitats, to the extent that they can no longer support native wildlife. In Marin, pesticides are a serious contributor to habitat degradation.

Habitat fragmentation refers to the cutting up of habitat into pieces separated by roads, houses, and other human creations. These fragments may not be large or connected enough to support the migratory voyage of monarch butterflies, which need places to rest and feed along their route.

Habitat loss affects certain plants and animals more strongly than others.

Generalist species like raccoons, cockroaches, and rats can live in a range of conditions and consume a wide variety of foods. Generalists are less likely than specialists to face extinction.

Specialist species like the western monarch can survive only on certain food and in certain places.

FIRST CRUCIAL ELEMENT OF MONARCH HABITAT: MILKWEED

Milkweed is the only plant on which monarch butterflies lay their eggs and monarch caterpillars eat nothing else. In addition to providing nutrition, milkweed contains toxic chemical compounds (cardenolides) that are sequestered within the caterpillar and adult butterfly. This toxicity, signaled by the monarch’s distinctive coloration and markings, make it toxic and distasteful to predators.

The best option for monarchs in Marin is narrow-leaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis). The only true Marin native, it begins growing in the spring, reaching 2 to 4 feet by summer. It blooms with nectar-rich pink and white flowers beloved by monarchs, bees and other pollinators.

The second best option is showy milkweed (Asclepius speciosa). Native to inland California, it was introduced to Marin many years ago. Local experts deem it an acceptable choice for private gardens in Marin, although not for wild areas.

Tropical milkweed (Asclepius curassavica) is not advisable because it hosts the highly toxic OE parasite. Read more about this parasite in the Predators section.

Check out this great video by Kim Smith of monarchs munching native milkweed.

Gardeners seeking plants that remain green all year sometimes avoid milkweed because of its winter die-back. However, if milkweed plants are interspersed with perennials, the garden can remain lush and green during the winter.

Additionally, some people are concerned about danger to household pets or small children from milkweed toxins. The chances are quite small of pets or children eating enough milkweed to become seriously ill, partly because it tastes bad. People should avoid touching their eyes if they handle milkweed because the sap can be an irritant.

To learn more, read this helpful article debunking four common myths about milkweed. More information about growing milkweed can be found in the home gardens section of the website.

Narrowleaf milkweed

Showy milkweed

CRUCIAL ELEMENT TWO: NECTAR PLANTS

Monarch butterflies are pollinators, along with other butterflies, bees, beetles, moths, and yes, even bats. Monarchs do not eat pollen. They consume nectar, which provides crucial sugars and fats for energy. However, as they move among plants consuming nectar, pollen dusts their body. The pollen is inadvertently transferred from one flower to another. This is a big and important job. Nearly three quarters of the world’s flowering plants require a pollinator to reproduce. So do two thirds of crop plants that produce our food.

Go to the home gardens section for lots of ideas about pollinator plants to put in your yard.

Pollinator Gardens and Monarch Butterfly Waystations

A pollinator garden includes plants designed to attract and support pollinators. Herbaceous plants, shrubs, and bushes can all act as pollinator plants as long as they have flowers for some period of time during the year.

A monarch butterfly waystation is a special type of pollinator garden that provides a place for monarchs to refuel and lay eggs during their migration journey. To fulfill this function, a monarch way station must have milkweed as well as nectar plants.

The term “waystation” refers to the fact that even a small habitat area can form part of a chain of habitats connecting inland areas to overwintering sites. These linked habitats enable monarchs to hopscotch through urban and agricultural areas, finding enough nectar and milkweed to fuel their migration.

Crucial Element Three: Nectar and Roosting Trees in Overwintering Sites

What do overwintering western monarchs need?

Between October and March, western monarchs gather along the Pacific coast to roost on eucalyptus trees, Monterey pines, and Monterey cypresses and occasionally on oaks, sycamores, and redwoods.

These trees provide wind protection and dappled sunlight, acting as a “thermal blanket and a rain umbrella.” Access to trees of varied height is important so that monarchs can find shelter during fluctuations in microclimate conditions such as wind and temperature.

Even though the monarchs are not moving around much during this period, they need fresh water and nectar for sustenance. Blue gum eucalyptus trees produce flowers during the overwintering season, providing a welcome source of nourishment.

Blue gum eucalyptus flower

How are the monarch’s overwintering sites being threatened?

In the overwintering sites in Marin, many roost trees have been cut down to make room for residential development along the coast. In particular, eucalyptus trees are targeted for removal due to their flammability. Also, because many were planted a century ago or more, they are vulnerable to falling, particularly during the rainy months.

While acknowledging these risks, monarch site management specialists emphasize the important role played by the eucalyptus as a roost tree, and recommend that it be protected while replacement options implemented.

How did Eucalyptus trees become widespread in Northern California?

Eucalyptus trees were introduced from Australia during the Gold Rush in the mid-1880s. The newcomers needed firewood as well as lumber for construction of all kinds. With a growth rate of 4 to 6 feet a year and a mature height of up to 100 feet, the trees were also planted to serve as windbreaks on agricultural land.

A second planting boom occurred in the early 1900s, when fears of a timber famine in the eastern US led to the cultivation of millions of acres of eucalyptus in California.

As it became apparent that eucalyptus wood was not suitable for construction, thousands of acres of eucalyptus were abandoned. Much of what we see today is what remains of this crop.

Learn more about the rise and fall of the eucalyptus in the Bay Area here.