Meet the Monarch!

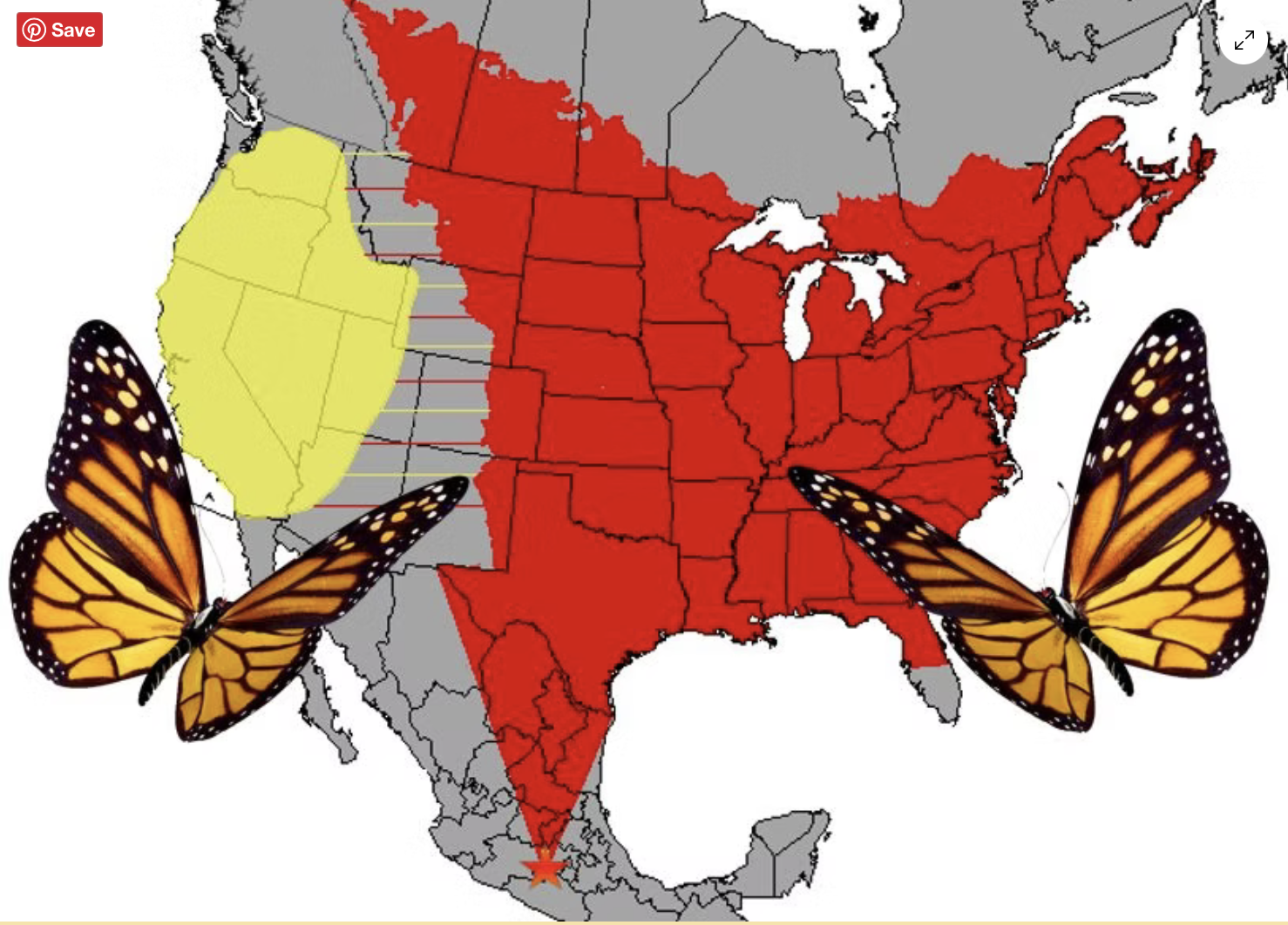

Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) are found across North America. They are geographically divided into three populations: western monarchs, eastern monarchs, and southern Florida monarchs.

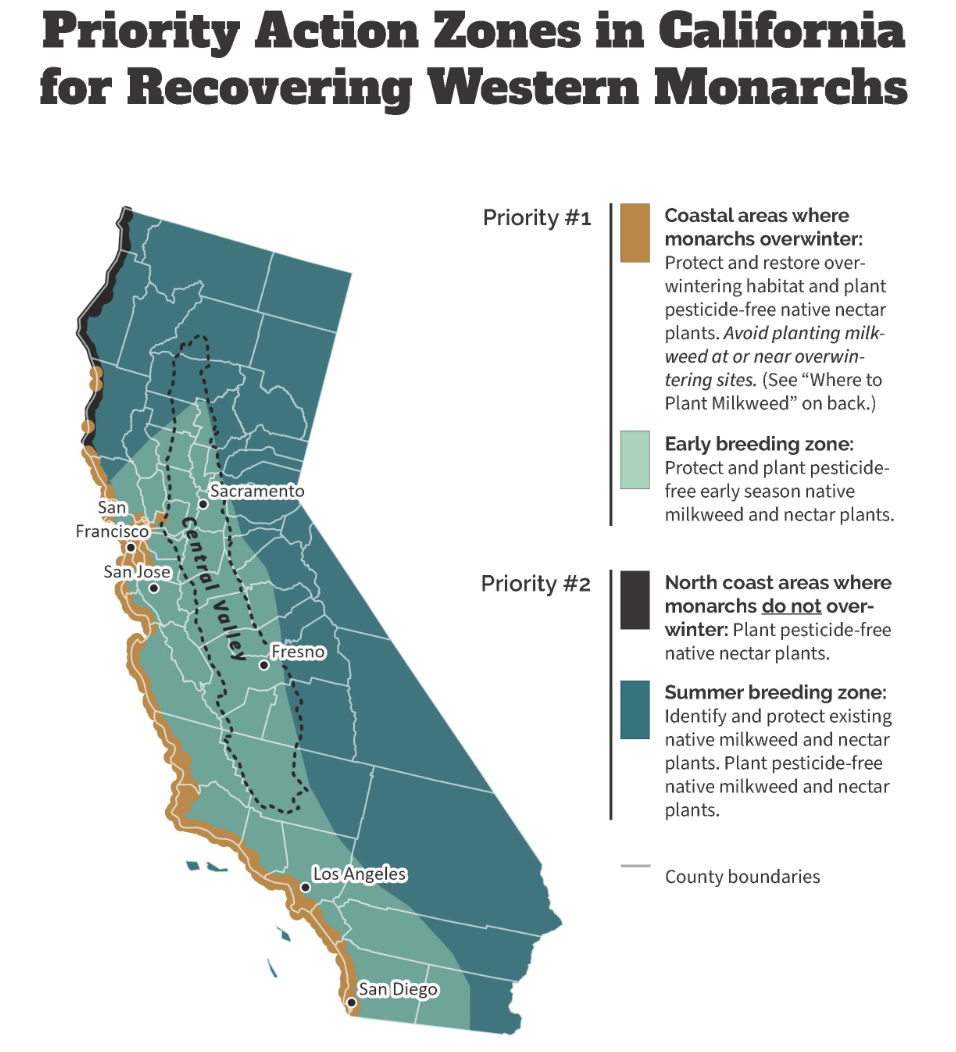

During the spring and summer months, the western monarch lives in California and other states west of the Rocky Mountains. In the fall, western monarch butterflies head west to overwintering sites along the Pacific coast.

The eastern monarch is found in the central and eastern US, and in southern Canada. It overwinters in central Mexico. The small southern Florida monarch lives in southern Florida and does not migrate.

Eastern and western monarchs are similar in appearance, but differ in terms of their physical stamina. Eastern monarchs fly three times as far as western monarchs during their annual migration and are capable of longer flights in a single bout. They also expend less energy when flying.

Interestingly, research suggests that eastern and western monarchs are NOT genetically different. There seems to be enough intermingling between the two groups to ensure that they all have the same genes. The difference in their flying skills appears to be a function of their environment, not their genetics.

Geographical distribution of western and eastern monarchs

Monarch Life Cycle

The life of a monarch begins when the female butterfly lays a tiny egg on a leaf. She secretes a special kind of glue to attach the egg firmly to the leaf. She flies from one plant to another, often laying hundreds of eggs over a 2-5 week period.

After about four days, a larva, or caterpillar emerges from the shell. It begins nibbling first on the egg shell and then on any available milkweed leaves.

In the long run, milkweed is absolutely essential to monarchs. It is the only plant on which monarchs lay their eggs and it is the only plant that monarch caterpillars eat.

But it is not easy for the newly hatched caterpillars to survive the latex sap that the milkweed leaves exude. The sap acts as a glue and can seal the caterpillar’s mouth shut or impede its movement. The little caterpillars protect themselves by digging a circular trench, which cuts off the latex supply to the area they are chewing on. You can see a caterpillar feeding within a trench in this photo from a blog post by Andy Davis.

The sap as well as stem and leaves of milkweed contains toxic chemical compounds (cardenolides). To the very small caterpillar, these compounds can be fatal if ingested. However, if the caterpillar is able to withstand their effects in the short run, the toxins are ultimately their most powerful means of self-protection. The toxins render the monarchs themselves poisonous, and so potential predators avoid them.

If all goes well, the caterpillar consumes a lot of milkweed over the next two weeks, expanding to roughly 2,000 times its original mass.

During this period, the caterpillar also molts five times, each time emerging in a new skin. These five stages are referred to as “instars.”

After two weeks, the caterpillar is ready to pupate. It spins a silk pad from which it hangs upside down, shedding its familiar yellow, white, and black striped skin for the last time. Its new layer of skin hardens into a pupa, or chrysalis.

After 8-15 days, the black, orange, and white wing patterns of the butterfly become visible. This is not because the pupa becomes transparent but because the wing pigmentation on the wings develops at the very end of the pupa stage.

When the butterfly emerges from the pupa, its abdomen contains body fluids but its wings do not, and this is why they are crumpled looking. The butterfly pumps fluids into its wings until they expand and stiffen. Then it flies off to feed on nectar plants. Learn more about the nectar plants that monarchs need in the section on home garden habitats.

Female monarchs have wider veins on their wings compared to males and their orange coloration can be slightly darker. Males have a black spot on a vein on each hind leg.

Becoming an Adult!

For the first several days after emerging from the chrysalis, adult western monarchs remain in their natal area, making short flights to nearby sources of nectar. Females begin mating during this period. Depending on the time of year when they are born, they may stay local or they may migrate west.

Monarch Migration and Overwintering

Western monarchs are well known for their epic migratory voyage, when they leave their overwintering sites along the California coast and head east for the spring, summer, and fall.

Successive generations during this migration period spread throughout the Western states, feeding on nectar, mating, and laying eggs.

The fourth generation heads back to the coast, where it spends the winter roosting with other monarchs, leaving the cluster only to find nearby nectar.

The Western monarch overwintering sites are mostly located within five miles of the Pacific Ocean between Mendocino and San Diego County. They look for large trees where they can shelter from wind, rain, and predators. They roost primarily on eucalyptus trees, Monterey pines, and Monterey cypresses. They can also be found on oak, sycamore, and redwood trees.

In February or March members of this generation head east, searching for milkweed and starting the cycle over again.

Cluster of overwintering monarchs